A Brief Life of Albert Schweitzer

By James Brabazon

Albert Schweitzer's achievements were manifold. Born in Alsace in 1875, his passionate intellectual curiosity, combined with huge physical energy, enabled him to win degrees in philosophy, theology and music at Strasbourg University, while earning a living as a Lutheran curate.

Two passions in particular ruled his thinking - a passion for the person of Jesus, and a passion for truth. In both fields he refused to accept ideas handed down by others that did not personally convince him. Thus he found himself in conflict with many of the thinkers of earlier times as well as those of his contemporaries and he was ruthless in his criticism.

In his sermons as a pastor, by contrast, he was gentle and sensitive; but again refused to say anything that he had not tested on his own heart, mind and soul.

He was driven by something more powerful than a striving for academic excellence: an insistent sense that he must pay something back for his happy childhood and his joy in university life. At the age of 21 this was so intense, it forced him to resolve that when he was 30 he would do something practical for humanity. But what? When the time came, in 1905, a missionary magazine article provided the solution. A doctor was urgently needed at a mission in the heart of the Equatorial Africa - at Lambarene, 150 miles up the Ogowe River in the Gabon. Instead of writing fat books for academics he would do something small "in the spirit of Jesus".

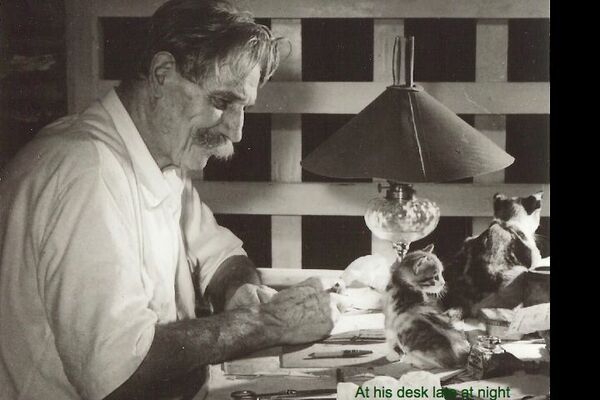

So he began to study for a fourth degree: in tropical medicine, while at the same time still lecturing on his degree subjects, preaching at his church and writing books on Bach, on organ-building, and, most importantly, on the ministry of Jesus.

In all these subjects he challenged conventional thinking, successfully overturning accepted views. In "The Mystery of the Kingdom of God", he laid out the proposition, that Jesus' words and deeds cannot be understood unless we accept that Jesus was convinced that the present order of things was about to end. The Kingdom of God would dawn and the world would be transformed. The lion would lie down with the lamb and there would be no more pain. But according to the prophets this demanded mass repentance from the people of Israel. When this failed to appear, Jesus decided that he must die on their behalf in order to usher in the Kingdom, resurrecting after three days. But the transformation did not happen.

This, of course, was rank heresy, and as a result, when he wanted the support of the Paris Missionary Society for his hospital at Lambarene, he was refused. All that they were prepared to give him was a piece of land at the mission. The money he needed for the medicines and equipment and their shipment to Africa he would have to raise himself.

The apparent paradox that Jesus' mistake did not lessen Schweitzer's admiration for him is solved when we realise that, to Schweitzer none but the greatest soul in history could have brought in a new testament, with its astonishing new ethical principles, based simply on the two great commandments to love: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God..." and "Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself". These positive commandments replace the ten negative commandments of the old testament. That was the Jesus that Schweitzer followed, regardless of what the church might say.

So he and his wife raised the money, went to Africa, and found that things were much worse than they had imagined. The Africans had every imaginable disease. The climate was devastating, the work endless. The hospital expanded and had to be rebuilt twice to his own designs on better land and built with his own hands with money raised by his own concerts. After World War One TB prevented his wife, Helena, from returning to Africa with him, but with various interruptions Schweitzer stayed there until his death at the age of 90.

But there was a further, crucial step in his thinking. In his philosophical and theological studies he had sought endlessly for a concept that he felt must be there, but which he could not find anywhere. What he wanted was a philosophical proposition whose truth was unarguable and which at the same time could be the basis for a useful life: an ethic that was not life-negating. It was in that primeval forest, with the huge forces of life and death locked in endless struggle, that in 1915 the phrase came to him - "Ehrfurcht vor dem Leben"; not quite adequately translated as Reverence for Life.

From then on, this was the foundation for all his thought and action.

It meant that every living thing, from an elephant to a blade of grass, deserves my reverence, for no other reason than that, like me, it lives and wants to go on living.

Schweitzer was a realist. He knew that, to live, a pelican must eat fish and a leopard must kill and eat its prey. Human beings are aware of the consequences of their actions, so must take responsibility for them, in the spirit of Reverence for Life.

He ran his hospital in this spirit, and similarly, when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, he used the opportunity to launch on the world stage the first major call to peace and nuclear disarmament.

He said "I made my life my argument"; and many who were there said that Reverence for Life worked. This, he claimed, was his legacy to the world, and it was undoubtedly one of the foundation stones for all the ecological movements of the 20th century including that of the Earth Charter in the 21st century.

Edited by Percy Mark 28. 12. 2016